When Stevie Moore’s child was murdered in Memphis, he wanted revenge. Instead, he vowed to stop others from acting on that impulse.

BY ELIZABETH VAN BROCKLIN

October 20, 2015

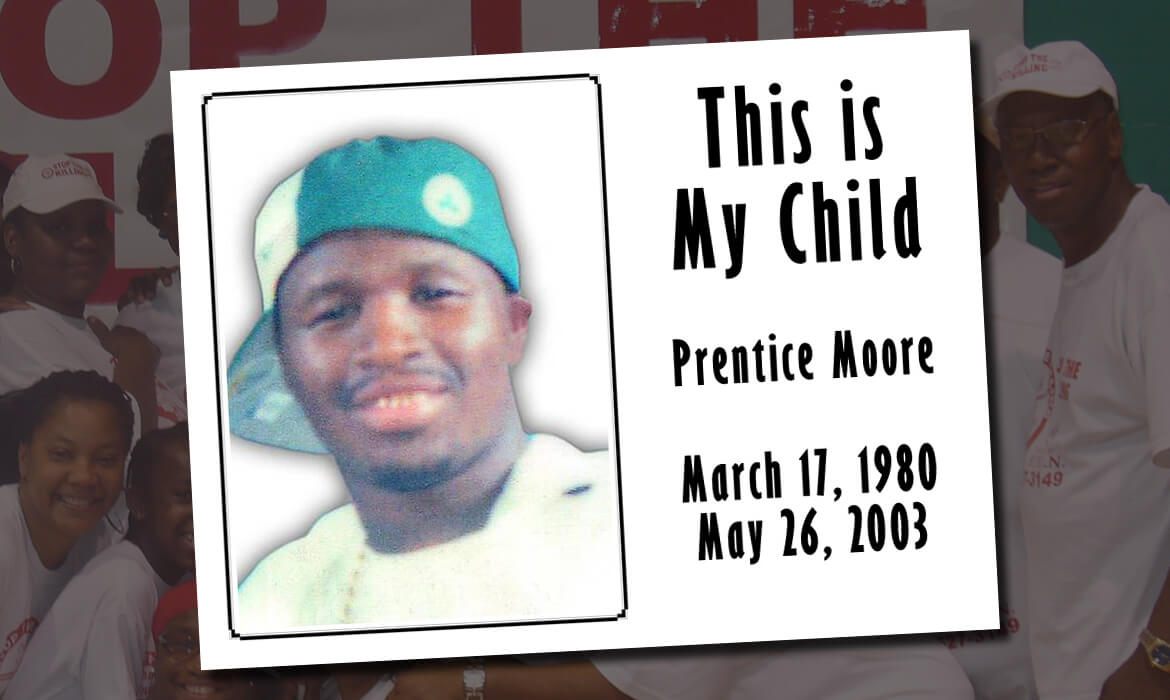

On a Sunday night twelve and a half years ago, Stevie Moore was hanging around his house in South Memphis, Tennessee, when his son Prentice came by. Moore asked Prentice about his plans for the night. Prentice said he and some other guys were going out to celebrate Memorial Day, which was the next day.

“I thought you had stopped going to the clubs,” Moore said. Prentice had claimed he stopped drinking and smoking, but Moore wasn’t sure he believed it.

“Dad, I don’t go to clubs,” Prentice replied, “but all the other guys are going, and Twin want me to go, so I’ma just go,”

“Okay, be careful.”

“Twin” was Prenston, Prentice’s younger brother by a few minutes. The pair had dropped out of high school at 18 to their father’s disapproval, and they’d been living with their mother, Moore’s ex-wife. Now they were 23, and they’d been coming around to visit their dad more often.

That night, the twins and some friends went to Denim and Diamonds, a western-themed nightclub in the Mid-South section of Memphis. There, by the pool tables, they got into a spat with some other guys — they’d had bad blood since one of them spilled beer on Prentice’s girlfriend months before. A little while later, a security guard escorted the brothers out. Joined by their cousin, the twins drove to a nearby Exxon gas station, where they often went to hang and flirt and play music loudly.

Minutes after pulling into the gas station parking lot, the guys heard shots over the thump of the stereo. Two of the men from club had followed them, one armed with a handgun and the other with an AK-47, and they were hurling a volley of bullets at the car. Prentice was in the driver’s seat, his brother was in the back. Just as he reached back to push his brother’s head down, a bullet shattered the back window.

STAY INFORMED

Subscribe to receive The Trace’s daily roundup of important gun news and analysis. (Not working, website is here to subscribe, https://www.thetrace.org/)

Prenston felt blood on his face. It took him a moment to realize it was coming from Prentice.

Moore didn’t hear anything until around 6 o’clock the next morning. A neighbor came over to tell him his son had been shot. He hurriedly put on some clothes and drove to the Exxon station.

Growing up in South Memphis, Stevie Moore had gotten into plenty of trouble. He spent his 20s drinking gin, selling dope, pimping women, and then serving time in three correctional institutions. When he got out of prison for the last time in 1981, he decided to straighten up and be a dad to his young boys. He founded a nonprofit, Freedom From Unnecessary Negatives (F.F.U.N. for short), focused on violence prevention and inmate reentry.

“I thought I’d been through so much, I’d been through jail,” he tells The Trace. “But that was the weakest moment of my life.”

When Moore arrived on the scene, his son was laying on the ground, face-down, with one outstretched leg inside the car. “I saw the blood just running down the street,” he says. “I ran to try to get him, and the police officer stopped me and he said, ‘Sir, you don’t need to see no more.’”

My job is this city right now is trying to calm it down and say, ‘Look, if you go shoot them, they come back and shoot somebody else, and y’all go back and shoot…When do it stop?’”

The next day, Moore went to the morgue and get a closer look at his son’s body. He saw the hole in Prentice’s skull where there should have been an eye. According to the police sergeant who investigated the crime scene, a 9mm bullet had blasted through the back window, lost momentum as it passed through Prentice’s head, and come to rest on the dash. Moore would learn from the autopsy report that true to his word, his son had not done drugs nor drank alcohol at the club. He would learn from his nephew Prentice’s last words: “Fool, I’m gone.” And he would see how Prenston’s light blue shirt had been soaked in his brother’s blood. Twelve years later, Moore still has the shirt folded up in a plastic bag in a drawer beside his bed. “Something to have from my son,” he says.

Amid the grief, Moore had to deal with another looming crisis. Prenston wanted revenge. The morning after his brother’s murder, he and a bunch of friends started to plan their retaliation.

“‘Please. I lost one son. You can’t do this,’” Moore recalls telling Prenston. Eventually, Moore convinced his son to go to the police and give a statement about the shooter.

All the while, Moore himself was not immune to a desire to strike back. “My oldest brother came to me and said, ‘I lost a nephew and you lost a son. Let’s us go take care of this business.’”

“For a slight instant I said, ‘Yeah, that’s right,’” he recalls. “You think those things when tragedy hits you.”

The thought passed quickly, replaced by an urge to do more. “That’s when I decided to stop the killing,” says Moore. “I said to myself these words: Even though I can’t bring my son back, I’m going to spend the rest of my life trying to save other people’s children.”

Prentice’s death prompted Moore to start a campaign called “Stop the Killing.” More than a decade later, the 65-year-old still attends to people all over the city, in the roughest of neighborhoods — North Memphis, South Memphis, Frayser, Whitehaven — mediating between parents and teenagers, teaching inmates, and reaching out to gang members. Despite a slight drop in the city’s violent crime this year (115 homicides so far compared with 122 last year), Memphis is still ranked America’s third most dangerous city by the F.B.I., after Detroit and Oakland.

Retaliation remains one of the Memphis’ biggest problems, in Moore’s opinion. “I see it every day,” he says. “Since my son’s been killed, I’ve been to over 100 funerals. From 2 years old all the way up. This is about retaliation. It starts somewhere else, but retaliation caused it to keep going.”

Sometimes, he makes a dent. Recently, Moore visited a mother who’d lost her son to gun violence. A group of the boy’s friends were outside the mother’s duplex, plotting. He listened to the group’s threats and anger, then pleaded with them to think about their next move. “Two things you can do” in these scenarios, he says. “Try to calm them down, or walk them through the process.” Moore sketched out what might follow a revenge killing — the lawyer costs, the court dates, the prison time, another one of their buddies dead.

“My job is this city right now is trying to calm it down and say, ‘Look, if you go shoot them, they come back and shoot somebody else, and y’all go back and shoot…When do it stop?’”

Eventually, two of the men in the group started to nod. One of them said he’d just had a baby, and didn’t want to go to jail. “Nothing else happened with that family,” Moore says. “I like to think I had a little something to do with that.”

Sometimes, though, he’s too late. In those moments, he often gets a call from a dazed young mother. She asks for help, and he goes to work raising money for the burial.